2. Methodology

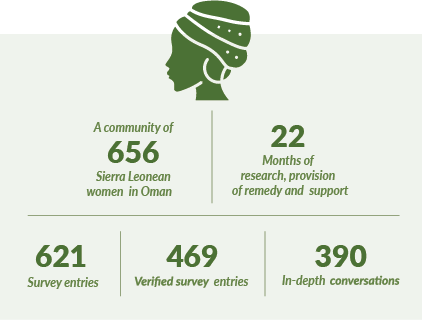

The objective of the Freedom for Our Sisters project was to support Sierra Leonean women victims of human trafficking or exploitation and to identify the gaps within different systems that allowed these issues to arise. For this, we carried out rigorous research, engaged with government entities, monitored grievance and accountability systems and government response, and collected RT & NRT data. Real-time (RT) data empowered us to respond quickly as we understood the problems as they were happening, and near real-time (NRT) data helped us to record a snapshot of historical data as it existed in the recent past. Up to date, we have engaged with a total of 656 women in this project. From these 656 women, we have received survey responses from 621 women, verified 469 from these surveys and engaged in one-on-one conversations with 390 women. The report findings are based on the 469 verified survey responses and from the 390 one-on-one conversations.

Before requesting participants to fill out the survey for data collection, we explained to them its purpose. The survey and conversations were conducted in English and all researchers were female. In the stories and comments cited, we have opted to withhold the domestic workers’ names and any other identifying details for their safety and to protect their identity. We have received consent from all women whose stories are shared in this report.

2.1 Project Framework

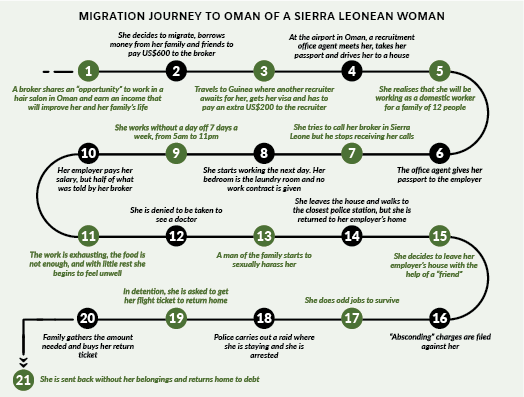

As a framework, we focused on the complete migration cycle of the Sierra Leonean women migrant domestic workers from recruitment to the arrival back in Sierra Leone. We examined reasons for migrating, recruitment, working and living conditions, repatriation and, to some extent, reintegration.

We used the following indicators and guidelines to identify victims of human trafficking, forced labour, and a set of human rights principles that cover the journey of a migrant worker from the following sources:

- The operational indicators of trafficking of human beings by the ILO

- The indicators from the ILO’s Special Action Programme to Combat Forced Labour

- The Human Trafficking Statistical Definitions, Prevalence Reduction on Innovation Forum, July 2020 (PRIF)

- The Dhaka Principles for Migration with Dignity (the “Dhaka Principles”)

2.2 Sources of Data and Documented Knowledge

This report is based on extensive investigations and monitoring, rigorous research, and deep knowledge of the context of migrant workers in the Gulf countries. The report’s findings are based on RT & NRT data and documented knowledge. The RT & NRT data has been obtained from a verified, tailored and very detailed survey of 649 women, one-on-one conversations with 390 women, and the evidence collected and analysed from October 2020 to August 2022 from Sierra Leonean women domestic workers in Oman. We have gathered the documented knowledge from our research on the ground, engagements with different government entities, monitoring of grievance and accountability systems and the direct assistance provided to this group of women victims of human trafficking, exploitation or other forms of abuse.

Domestic Workers

Survey

For the project, we launched two surveys: an initial survey to define variables, and a second survey that contained questions tailored to this group and was accessible to those who were not able to read or write. The initial survey includes 135 data entries and the second survey includes 621 data entries from which 469 are verified.

The survey helped capture high-level indications of potential human trafficking or forced labour. Through the survey, we collected general information related to the recruitment process, working conditions and current conditions, as well as more detailed information such as information about the recruiter, recruitment fees paid and source of this money, detailed information on working hours, sleeping arrangements, access to internet, and types of violence, experienced, among others. Survey participants could also submit photographs, videos, and audio clips.

Conversations

We knew that a survey alone would not capture all the elements and details that are woven into and between issues affecting women domestic workers. It was also important to have conversations to hear the stories as told and experienced by the women directly, to confirm whether they were victims of trafficking or other forms of exploitation or abuse, to understand the support that they needed, and to capture other details that often go unnoticed. Conversations took place over periods ranging from a few days to as long as 10 months.

Our approach is to have victim-lead conversations, rather than interviews. In these conversations, women articulate their primary concerns or struggles. Many of these conversations go into further detail, thus capturing issues that often are not shared through interviews, such as the deeper reasons for staying in or leaving abusive employer relationships, their dreams and hopes and details of physical and sexual abuse. We also use conversations to assess vulnerabilities, which was important given the large number of women requesting support and the limited resources available.

All engagements with the women took place via WhatsApp or via phone, the most accessible and easy-to-use mediums for the women. We held the conversations mainly via voice notes because of the inability of most of the women to read and write. The purpose of using WhatsApp (versus in-person conversations) was not only because of COVID-19 restrictions but also because many of these women are not accessible in-person as they are inside their employer’s home or in their recruitment office. So, regardless of COVID-19, they would not have been reachable through any other means.

Employers and Recruitment Offices in Oman

We also had conversations regarding the cases of at least 36 women with employers and staff from recruitment offices. These conversations took place when a woman was under their sponsorship and wanted to return home. These efforts helped us, in particular, to better understand the gaps in the system that keep a domestic worker in situations that can be considered Forced labour.

Governments

We held extensive conversations with government officials from both Oman and Sierra Leone. Throughout the project, we worked with the Embassy of Sierra Leone in Saudi Arabia. We also spoke to and coordinated with different government agencies in Oman to provide support to Sierra Leonean women, including, for example, police officers in different detention centres across Oman, and the Ministry of Labour.

Monitoring

We monitored grievance and accountability systems and government responses in different situations to understand what was accessible for the women who needed support in Oman. We tried to access, or guided the women to access directly, all the grievance mechanisms in the country and documented the process and response. Police raids, detention and deportation processes were also documented.

Secondary Sources

We conducted thorough research and analysis of relevant laws, decrees, policies, circulars and documents in Oman in English and, when necessary, in Arabic. For Sierra Leone our secondary research included: the National Action Plan Against Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children (2021-2023), the Sierra Leone Labour Migration Policy, the National Review Report of the Implementation of the Global Compact for Migration in Sierra Leone, and the National Migration Policy for Sierra Leone. A review of other secondary sources also supported this research, such as trafficking in-person reports, Universal Periodic Reviews and reports from NGOs and other institutions.

2.3 Methodology used for Verifications and Calculations

Verification of Survey

The information submitted through the survey by the community was verified before being used in this report. The verification process helped to validate the information submitted and thus the information analysed. It included the deletion of data entries that were not relevant (entries of men, people of other nationalities or people in a different destination country) or duplicates. After this verification process, some answers to specific questions were further analysed for incongruences and comprehension. If answers were not congruent (e.g. she stated that she arrived in Oman after the date she filled out the survey) only the incongruent answers were omitted from the analysis. This was also the case for missing survey items: only that answer was excluded and the rest of the survey was retained. As a result of the verification and analysis process, a different sample size was used for each finding and, unless mentioned otherwise, the sample size used is the complete verified survey sample of 469 women .

Prevalence of Human Trafficking Calculation

For identifying the prevalence of human trafficking, we used the guidelines set forth by the Human Trafficking Statistical Definitions: Prevalence Reduction Innovation Forum, July 2020 (PRIF). According to these guidelines, a person can be identified as a victim of trafficking if he or she is found in any of three scenarios that are a combination between “medium” and “strong” indicators in different categories. For this calculation we have surveyed two groups of women: 1) those that were, at the time of the survey, still engaged in labour services for their visa sponsor, recruitment office, or with a new employer placed by the office staff (24%) and 2) those who had left their employer (76%). Since we were analysing a sample with both those currently experiencing indicators and those who had recently experienced indicators, we calculated the prevalence using both the calculation for “Sex Trafficking, or Forced Labour, Adult, Flow” and the calculation for “Sex Trafficking, or Forced Labour, Adult, Stock”.