We received verified survey responses from 469 Sierra Leonean women, the majority (94%) of whom migrated to Oman between 2019 and 2021. All women were between the ages of 17 and 43 but the majority were between 23 and 32 (88%) (born between 1990 and 1999) at the time they filled out the survey. Of those surveyed, 76% had left their employer and were “outside”, 12% were working with their employer and 2% were in an office.

According to the latest information from the Government of Sierra Leone, the number of Sierra Leoneans in Oman is estimated to be approximately 4,335 as of October 2021. As such, our verified surveys may have covered a sample size of 11%.

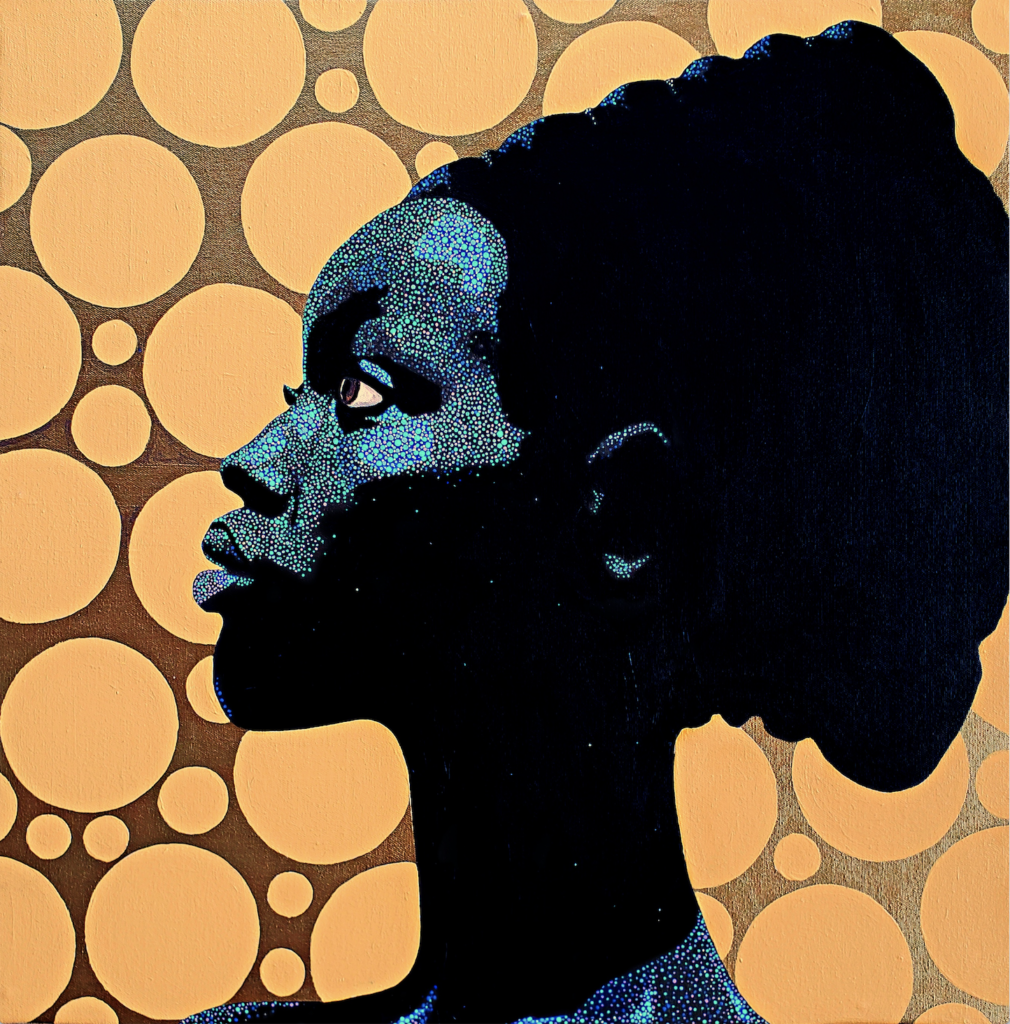

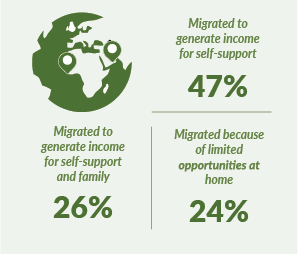

Reasons for Migrating

Sierra Leone is one of the poorest countries in the world with an average income of US$1.40 a day based on data from the year 2020. This group of women had limited economic opportunities in their home country as a result of the current economic situation in Sierra Leone: economic growth is extremely volatile, which limits job creation and stability. According to the World Bank Database, 50% of the national income is attributable to only 20% of the population and thus has only a limited effect on poverty reduction and employment generation. One-third of the working-age population is not employed, especially women. And when employed, the gender gap in earnings and wages shows that men earn three times as much as women.

“The reason why I live my country to come and work in Oman is that l came from a poor family so I come here for me to work and provide for my family and my children I come from a family of ten and I and d [sic] eldest I was once a student but my parents couldn’t afford to pay for me and my siblings so I drop out of school to learn taloring so that l can be able to put food on table my two parents have carry age so what l get at from the tailoring I feel [feed] my family but since corona virus come to our country no more work and we were going through a lot in time of food cloth shelter etc so that give me d cause to live my country and come to work in Oman so that I will be oble to provide for my family”

From the 469 verified surveys, the main reasons for migration were:

- To generate income for self-support (to work, find money, further their education, start a business upon return, or build a house) – 47%

- To generate income for self-support and family – 26% – including

- Securing a better education for their children now or in the future

- While Sierra Leone rolled out a free education program in 2018, anecdotal reports and an analysis of the 2020 School Census report indicate that parents are still asked for significant financial contributions for their children’s education.

- Paying for ongoing medical care for a chronically ill family member

- Only children under five and pregnant and nursing mothers have access to free health insurance. All others must pay for their healthcare out-of-pocket, including the bribes often required to access care, constituting a large financial burden for many Sierra Leoneans.

- Securing a better education for their children now or in the future

- Limited opportunities at home, poverty and hardships – 24%

Important elements to highlight, contributing to migration to Oman, is the loss of the main family provider (a parent, husband or sibling), and the participants’ inability to secure a sufficient job to provide for themselves and their families.

“I lost my parent during the civil war in Sierra Leone so there was no hope for me because I did not want to misuse myself through prostitution and drugs so I decided to travel”

It is also relevant to note that West Africa suffered from an Ebola outbreak between 2014 and 2016 which significantly affected a lot of livelihoods. For example, in Sierra Leone, over 8,706 people were infected with the virus, and an estimated 3,590 died. The Ebola crisis affected Sierra Leoneans’ livelihoods, jobs, and income across all sectors and over 3,880 jobs were lost in a single year. Those surveyed and interviewed often cited the loss of a breadwinner as a reason for migration.

“It’s so sorry. I leave my home country just because of Ebola, various (sic), Ebola various kill my mom and my father. From then I started to live with my uncle, and also my uncle too started to treating me like that and in that time I even started to express something like frustrating. So all that brings me the cause to travel.”

Migration Routes

In early 2019, Sierra Leone banned all recruitment of Sierra Leoneans for employment abroad. During a press release on April 30th, 2021, the Ministry of Labour and Social Security stated “The ban was instituted in 2019 as a means to curtail the uncoordinated and unregulated inflow and outflow of Migrants, which were mostly facilitated by Non-Registered Under-Ground Overseas Recruitment Agencies”. The ban’s aim was to prevent labour exploitation of Sierra Leoneans abroad. However, instead, it created a flourishing illegal recruitment business and fuelled migration through informal channels, thus increasing human trafficking. This ban was lifted on April 21st, 2021. From a sample size of 406 women from the verified surveys, 90% of the women travelled during the moratorium, 2% between May 2017 and December 2019 and 7% after the moratorium until April 2022 (the latest arrival in our data set).

Travelling right before, during, or after the ban made no difference in the recruitment process and migration routes. Those that travelled outside of the ban were still deceived, paid recruitment fees and travelled via the same geographical routes. We understand that direct flights did not operate from Freetown, Sierra Leone to Muscat, Oman during this period. Most flights we are aware of went through Burkina Faso, Ghana, Nigeria, Turkey, Egypt, and UAE. In our research and from a sample size of 458 women of the verified surveys, we found that 84% of the women first travelled to another country before departing to Oman, with border crossing by land to Guinea (58%), to Senegal through Guinea (36%) or to Liberia (1%) before departing for Oman. This is primarily because most of the women travelled during the moratorium period and would not have been allowed to travel from Sierra Leone. Furthermore, the price of a ticket from Freetown to Muscat is almost double the price of one leaving from Conakry, Guinea. A single trip ticket from Freetown to Muscat is approximately US$900 compared to US$500 when departing from Conakry to Muscat. Prices from Dakar, Senegal were slightly cheaper than from Freetown, but only by approximately US$100. Most of the women got their travel visas while in Guinea or Senegal.

The U.S. Department of State Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Report from Sierra Leone 2021 (Tier 2) reported that “Traffickers move women through Guinea, The Gambia, Liberia, and Senegal en route to exploitation in the Middle East”. The 2022 TIP Report from Guinea also stated this:

“Reports indicate trafficking networks fraudulently recruit Guinean, Liberian, and Sierra Leonean women for work abroad, using the Conakry airport to transport victims to exploitative situations in Kuwait and Qatar. In a previous reporting period, an international organisation reported an increase in fraudulent recruitment for forced labour in domestic service in the Middle East, especially Egypt and Kuwait”.

These two statements are consistent with our findings. Sierra Leonean women were recruited in Sierra Leone and travelled to Guinea or Senegal with false promises before travelling on to Oman. In some instances, once in Guinea or Senegal, they were given the choice of where to travel. These choices were mainly Iraq or Oman. The time spent in either of these countries varied from a few days to a few months and their “agent” or second “agent”, who they paid, was also present in these countries.

From the 84% of the women that did not travel directly to Oman, our findings showed that the most common route (58%) was through Guinea and the second most common through Senegal (36%). Additionally, 3% travelled through both Guinea and Senegal. A smaller percentage transited through other West African countries (Liberia – 0.8% and Togo – 0.3%). Four women (1%) travelled from West Africa to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) before crossing into Oman. During our conversations with the women, we found that women that had arrived in the UAE with a tourist visa were then smuggled to Oman via illegal border entry points.

In total, 16% of the women reported travelling directly from Sierra Leone to Oman.

According to the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children, otherwise known as the Palermo Protocol, there are three elements that need to be satisfied to constitute trafficking – the act, the means and the purpose.

Oman signed and ratified the Palermo Protocol in 2005 and passed a Trafficking in Person law in 2008. Oman also created the National Committee to Combat Human Trafficking (NHCCT) in 2009. In August 2020, the Ministry of Labour established an anti-human trafficking unit. From April 2021 to March 2022 Oman identified 13 women and 1 girl as victims of trafficking, all related to sex trafficking and none for labour trafficking. In addition, the 2022 TIP report states that “the government has not reported any forced labor of migrant workers, including domestic servitude, prosecutions in the last three years”.

The NHCCT also created an action plan period 2018-2020 where they created awareness-raising campaigns and provided training on how to combat human trafficking. A national symposium on human trafficking was organised, and divisions specialising in human trafficking were established. The action plan period 2021-2023 promotes finding appropriate solutions and strategies to address, prevent and combat human trafficking, strengthen cooperation and support efforts to monitor, investigate and address human trafficking, and to provide care for victims.

However, despite Oman’s efforts to strengthen its efforts to combat human trafficking, its regulations related to domestic work prevent the Sultanate from effectively addressing human trafficking. Additionally, due to the lack of monitoring and enforcement of the rights of domestic workers and the unilateral control held by employers and recruitment agencies over the workers under the kafala system, domestic workers are at high risk of being victims of human trafficking or working in conditions that amount to forced labour.

“They told me that I we will going to France and get a good job that will help me an (sic) my family but it was all setup 😭😭😭 I was dissapointed (sic), I want to go home back”

In fact, our research has shown that human trafficking of domestic workers from Sierra Leone to Oman is widespread. Using the guidelines set forth in the PRIF, we have analysed our sample group across the following categories of indicators for the prevalence of human trafficking:

- Recruitment

- Employment Practices and Penalties

- Personal Life and Properties

- Degrading Conditions

- Freedom of Movement

- Debt or Dependency

- Violence and Threats of Violence

Within each category, there are a number of indicators that constitute either a “strong” or “medium” indications of the prevalence of human trafficking.

We were able to identify a prevalence of 99.8% of human trafficking from our verified sample (468 out of 469 women). The vast majority (93.4%) have been identified as victims of human trafficking due to the restrictions on their freedom of movement or communication. An additional 6.4% of those that did not fall in the prior group were then identified as victims of human trafficking due to the prevalence of a number of other indications for human trafficking from the above-mentioned categories.

In relation to the indicators for prevalence of human trafficking mentioned above, our findings showed that the majority of verified survey respondents (78%) experienced deceptive recruitment. They were deceived either about the 1) type of work they were being recruited for, 2) work conditions, 3) salary they would be receiving monthly, or 4) country that they were being recruited to. Recruitment fees were paid by 93% of the total verified survey sample and the vast majority of the 469 women we surveyed were also subjected to working conditions that constitute exploitation. These findings include: no day off (99%), long working hours (80% worked between 16 and 20 hours a day), wage theft (60%), restrictions of movement (91%). In addition, 26% of the women were locked in a room at some point. Many (84%) had their passports confiscated. (Of those who did not have their passport with them, 85% said their passport was with their employer, 8% with their recruiting agent, 5% did not know and 1% had lost it.) Many reported threats, physical abuse (57%) and sexual abuse (27%). Finally, 55% of the women had their belongings searched by their employer, and 35% did not have their own room to sleep and slept in public spaces such as the kitchen or living room (those that had their own room often described it as a “storage room”).

“He [told] me that I will come work in Oman for 350 dollar but now the money is not like that”

Forced labour is defined by the ILO as “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily”. To put this definition into the context of this project, this means a Sierra Leonean woman is in a potential forced labour situation if:

- She was deceived during recruitment (i.e. “not offered [her]self voluntarily”), and

- she cannot leave her job without penalty (i.e., “exacted…under the menace of any penalty”).

From the 469 verified survey entries, 78% of the women were deceived and did not consent to the working conditions that they found themselves in. In Oman, there are two broad categories of penalties for leaving your employer:

Systemic penalty. In Oman, under Decree 189/2004 regulating domestic work, it is a crime for domestic workers to leave their employer without permission. If an employee leaves their employer, the employer is obligated to file “absconding” charges. Once a worker has “absconding” charges filed against her, she is considered a criminal and is barred from leaving the country voluntarily, and she is subject to detention, arrest and/or deportation.

Illegal penalty. We have consistently witnessed recruiting offices and employers punishing workers who request to return home or change employers. Punishments include physical abuse, verbal abuse, request for “release money”, salary reduction, withholding of salary, increased workload, increased surveillance/invasions of privacy and threats of detention and/or deportation.

To determine if survey participants are victims of forced labour, we also look at both the definition above and ILO’s forced labour indicators. Using these two tools, we have identified that the vast majority of the group of women surveyed and/or interviewed work(ed) in conditions that are consistent with forced labour indicators. From our verified survey responses we found:

- Indicator: Excessive overtime

- 99% reported that they do not have a day off per week

- 80% worked between 16 and 20 hours a day. 63% had one break per day while 30% had none. Of those that had breaks, 55% had between 1 and 1.5 hours while 30% had two hours.

- Indicator: Retention of identity documents

- 84% stated that they did not have their passports with them passport confiscation (85% of the womens’ passports were with their employer, 8% with their recruiting agent, 5% did not know and 1% had lost it)

- Indicator: Deception

- 78% were deceived to be recruited

- 64%were given false information about wages

- 64% were given false information about the nature of work

- 21% of those who received false information about the nature of work, received false information about the working conditions as a domestic worker

- 15% were given false information on the country of work

- Indicator: Abusive working and living conditions

- 91% were not able to refuse work, even when they were not feeling well

- 80% were not able to go to the doctor

- 58% reported that their employer did not give them enough food to eat, while 4% said their employers did not provide them with food at all

- 35% did not have their own room, some often sleeping with elderly relatives they were caring for, or on the floor in the kitchen or living area

- 55% said that their belongings were searched, invading their privacy

- 65% worked for more than one family

- Based on the 390 conversations with the women, a number of them also reported having to work in unsafe working conditions (e.g. cleaning ceiling fans with tall ladders and being susceptible to falls)

- Indicator: Debt bondage (see Recruitment fees and Wage theft and salary deduction)

- 93% paid recruitment fees. These women often find it difficult, if not impossible, to leave their employer because of the debt they have placed on their families or on themselves

- 60% experienced wage theft. Their salaries were not paid, not paid every month, and/or not paid completely

- Based on the 390 conversations with the women and on the negotiations with the employer or recruitment office for the release of the woman, in the majority of these instances the employers and/or recruitment agencies requested payment, or to work without pay to “repay” either the employer’s payment to the recruitment agency or the recruitment agency’s costs to bring them to Oman. We rarely encountered an employer or recruitment office who would allow a worker to leave before the end of a two-year period of service without repaying some of their recruitment fees, regardless of the working conditions that they might be in. In the vast majority of these cases, recruitment offices and employers told workers they could return home if they paid for their return ticket and paid “release money”. However, these payments are not financially viable for the vast majority of workers (see Reasons for migrating and Recruitment in Sierra Leone)

“Sponsor called me and asked him to give the money to him. […]. We took the money to the station because the cops they tell to us give the money. […] But now for ticket, we do not have money again”

- Indicator: Restriction of movement

- 91% were not allowed to leave their employer’s property by themselves

- 26% were locked in a room intermittently, most often at night, either in their employer’s home or in their recruitment office. In recruitment offices, they were generally locked in a room with other people

- Indicator: Withholding of wages

- 60% experienced wage theft

- Indicator: Intimidation and threats

- 77% reported they had been humiliated, discriminated against, or insulted. Most often, they reported that their employers made racist remarks or negative comments about their appearance or body odour.

- From our conversations with the women, it was found that threats of calling the police or withholding part or all of the worker’s salary were the most common forms of intimidation and threats. Our conversations also revealed that employers and office staff intimidated workers by asserting their status as citizens of Oman versus the worker’s status as a migrant worker. These threats were most commonly made when workers voiced concerns about their working conditions or wished to go back to Sierra Leone

- Indicator: Physical and sexual violence

- Abuse was perpetrated by both employers and staff from the recruitment office.

- 57% reported physical abuse

- Slapping and pushing were the most common forms of physical abuse. Throwing objects, flogging, burning, and puncturing of the skin were also inflicted.

- 27% reported sexual violence

- This mainly happened at the employer’s home where the perpetrator was a male family member. There were instances when wives knew of the abuses and others where the abuser threatened to harm the worker if anyone else found out. Sexual abuse included perpetrators exposing themselves, exposing the victim or touching the victim in private areas, and rape.

- 57% reported physical abuse

- Abuse was perpetrated by both employers and staff from the recruitment office.

- Indicator: Isolation. Under Oman laws and visa regulations, all domestic workers must live with their employers, a practice that isolates them from the rest of society

- 50% were not given access to Wi-Fi

- 49% had phones or SIM cards taken away at some point, preventing them from communicating with their families or seeking support

- During our conversations with the women, some shared their locations that pointed to homes in remote areas of Oman, where they were cut off from the outside world as they had no access to transportation

- Indicator: Abuse of vulnerability

There are other vulnerabilities affecting the community of Sierra Leonean women:- Dependence: the vast majority of women are/were dependent on employers for housing, medical care, and food

- English literacy: from our conversations with the 390 women, the vast majority were not able to read or write English. All of our communications had to be done via voice messages (unless these were simple sentences such as “ok” or “how are you?”), and the survey had to support their literacy level as well. The literacy rate in Sierra Leone is low: 65% of Sierra Leonean women aged 15 and above are not able to read or write

Who is the Recruiter?

The opportunity to migrate was introduced to the women by different types of recruiters. Some were individual brokers, others were friends or family members. The majority (61%) of women were recruited by an individual broker, referred to as “my agent” by the women. The other 22% were recruited by friends, and 7% by family members. Only seven women were recruited via social media or traditional media. Most individual brokers were men whereas friends and family members were men and women.

“Agent said if you go there and work i will help you, you will find money for your children. work for me for 3 months and pay me money.”

For the individual ‘agents’, all the information that the women had from them was their name (sometimes only a first name or pseudonym), phone number and the location from where the ‘agent’ would operate. None of the women were able to provide an office address or a recruitment agency name. Many women told us that once they were recruited, it was common for the recruiters (the agent, friend, and family member) to change their phone number and/or block the worker’s phone number, preventing any further contact.

“He is a very criminal man I told him that I don’t want to work in Oman but he said there is no problem as soon as I arrived in Oman I told him what I am going through he blocked me till now”

We also received a lot of anecdotal information suggesting that recruiters are targeting women living outside of Freetown in smaller cities, towns, and rural areas, as their deceptive tactics have become more well-known in populated areas in recent years.

The women also reported that multiple recruiters are clearly working together. For example, a woman would be recruited in Sierra Leone and her recruiter would arrange her travels to Guinea to be picked up by a second recruiter. In Guinea, this second recruiter would process her documents and arrange for her to travel from Guinea to Oman.

While it is not possible to prove definitively in every case that recruiters always knew about the working and living conditions they were recruiting the women into, it is highly likely that most had a strong awareness of the common grievances and experiences of women in the domestic work sector in Oman, given the number of women who told us that they reported their distressing experiences of abuse to their recruiters, who in most cases failed to help in any meaningful way.

“I don’t know the agent, it was a friend that talk me into it. The (sic) painted the whole thing to be interesting. They told me it’s just to clean the house and cook. But on getting here it was a slavery work to extend that I can’t even talk to my children I left back home.”

Recruitment Fees

According to the Employer Pays Principle, the ILO Guiding Principles and Operational Guidelines on Fair Recruitment, and the Dhaka Principles, private recruitment agencies in sending and receiving countries are not supposed to charge, directly or indirectly, in whole or in part, any fees or costs to workers. However, according to our findings, 93% of women paid illegal recruitment fees. Unfortunately, the majority of the women saw these payments as normal since they were joining a “programme” that would help them find work or study opportunities.

“I give my agent 4 hundred dollars and I give The Man who board (sic) me and other [another] 4 hundred dollars and in the airport I give 1 hundred dollars again”

Of those who paid recruitment fees (sample size: 395), the average fee was US$1,320 and the median was US$700. The majority (60%) paid between US$500 and US$1000, 19% paid less than US$500, 7% paid between US$1,501 and US$5,000, and 6% paid more than US$5,000. Those who believed they were going to the US or Europe paid an average of US$425 more than the average person who was told they would be going to Oman. Those told they were going to Turkey, paid an average of $165 more.

“I pay seven hundred dollars and he told me that I have to pay for my tickets and boarding fee”

What should theoretically happen, is for the recruitment office in Oman to pay the recruitment agency in Sierra Leone for their recruitment support, and the employer pays the recruitment office in Oman for their services including flight ticket and visa expenses. However, in reality the worker pays the recruiter in Sierra Leone. Then, in Oman, the employer often passes on the recruitment fees that they paid the recruitment office to the worker by making her work for 2-4 months without payment either at the beginning of the contract or before they leave the employer. For workers that no home is found, or interim, they are sent by the office to work for different households for short times for which then the office withholds their salaries.

“I paid about $800 [USD] for the visa and everything but on getting here when they were treating me like slave, if I complain my sponsor will tell me that he bought me because he did my visa and bought my ticket. So the whole thing got me confused based on the money I paid to my agent”

Also, it is important to note that, as the vast majority of women paid a significant sum of money to migrate and have already invested a lot, it is very difficult for women to return home even if they can, as they know that if they return their debts still need to be paid. As a result, many domestic workers stay in exploitative working conditions with the hope that they will eventually be paid or working conditions will improve. This can be described as a situation of debt bondage; an exploitative situation from which women cannot escape from because of debt, and which often leads to situations of forced labour.

Sources to Pay the Recruitment Fees.

For most Sierra Leoneans, paying the recruitment fee requested is not an easy task. Sierra Leone is one of the economically poorest countries in the world, ranking 180 out of 187. The average income in Sierra Leone is US$509.37 per year, last recorded in 2020. That means that the recruitment fees paid on average are equivalent to one year’s work.

“I sold my clothes,my refrigerator,my television,my sitting chairs and i also sold all my goods for a cheaper price just to complete the money for my traveling”

To pay these recruitment fees, 34% of the Sierra Leonean women in Oman borrowed from their family, 14% sold their personal belongings, 18% borrowed from another person, 3% got credit from an agent and 5% used their savings. About 15% of the women took out a bank loan from a bank in Sierra Leone, which indicates that they had high hopes that the opportunity would help them generate enough income to repay the loan and the interest while being able to support themselves and their families.

“I sold one land i acquired and I also gave out my shop and sold everything I had inside to another person”

“Well I work for four months for my agent”

Women who borrowed money to pay recruitment fees were hesitant to return to Sierra Leone, despite being in a difficult situation in Oman. Women who borrowed money from a bank to pay these recruitment fees were concerned about potentially being arrested upon returning. Those who borrowed from friends or family were concerned about the social/relational implications.

Deception at Recruitment

Deceiving individuals at the point of recruitment for the purpose of exploitation is a key element of human trafficking. Deception was the most common means of recruiting Sierra Leonean women to Oman.

Most women had limited access to information about working or studying abroad and relied on the information provided by these agents, friends, and family. For example, one woman reported that her friend (who recruited her) was working in Kuwait, and her friend told her that she would be paid “huge money.” Another reported a similar story; where her friend was working in Lebanon and she spoke highly of her work experience.

“This she was working in dubai in a factory as a fruit packing then she tell my about how life is getting better for her then she tells she will help me to work in the same place as a fruits packing then she directly connects me with her agent so I will go and work with her in dubai, but not knowing that am coming to Oman to work as a maid.”

Of the 469 women, 78% of the women were deceived. Our research indicates that 15% of the women were deceived about the country they were migrating to, an extreme form of deception. Recruiters had told them that they were going to migrate to and work in the United Arab Emirates, particularly in Dubai (38%); Europe, the United States or Canada (23%); Turkey (15%), Kurdistan (9%) or Kuwait (8%). Others were told only that they were migrating to other African countries, like Senegal. This suggests that recruiters used these countries to create a false narrative of security to recruit women. For example, women who decided to migrate to Turkey or the UAE often knew people who have travelled or worked there, so they felt more comfortable with the decision to migrate for work. These women found out that they were travelling to Oman until they saw the ticket or they had arrived.

It was also found that 64% of the women were deceived about the type of work they would be doing in Oman. Recruiters promised work opportunities in supermarkets, hair salons, hospitals, hotels, and restaurants. This means that the vast majority of this group of women did not know that they were being recruited to work as domestic workers. A total of 21% of the women reported that they had agreed to work as domestic workers, but when they arrived the actual conditions of work were different from what had been promised.

“They tell me that I’m coming to work in a big company with different people from different countries”

In addition, 64% of the women reported that the salary they received in Oman was less than the salary they were promised before travelling.

“All what the agent told me is lie, he said only one babe I take care of salary 180 Riyals but when I reached Oman not true they pay me 80 Riyals, no rest, no sleeping, change diapers a big woman”

Additional types of deception we documented included recruiters in Sierra Leone providing workers with misinformation about the length of their contracts/commitment, and telling workers that they would have the freedom to change jobs, employers and, in some cases, their destination country. Many of the women were also under the impression that their recruiters would continue to support and advocate for them while they were working in Oman. However, we never documented a case where a recruiter provided any kind of support to a worker once she was in Oman. In fact, in most cases, recruiters blocked the phone numbers of the women once they arrived in Oman.

“He told me that im coming to work as a nurse”

A large number of Sierra Leonean women in Oman felt disempowered and deceived by this experience. When asked if they wanted to know how to refer their recruiter to the police, 18% of them responded ‘yes’, 22% ‘not yet’ and 42% ‘no’.

Potential Fabrication of Medical Tests for Obtaining Visas

To obtain a visa, migrant workers must be free from communicable diseases such as hepatitis, HIV and TB. In addition, those seeking domestic workers’ visa, must also undergo a pregnancy test and test negative to obtain a visa before arriving. All migrant workers that want to work in the Gulf countries are required to do medical tests before migrating to ensure that they can obtain a visa upon arrival. However, in the case of Sierra Leoneans, we found four (4) women who were recruited and travelled to Oman and did not pass the medical test upon arrival. According to the women, they had all undergone medical tests in Sierra Leone and we assume that either the tests were not done correctly or they were lied to regarding their results. The issues found included TB, HIV and pregnancy.

In one instance one woman reported that the clinic where she did the test had said that there was something wrong, but that she was ok to travel.

Upon arrival in Oman, a woman is picked up from the airport, her passport is taken from her and she is usually taken to the recruitment office, also known as the “office” or directly to the employer’s home if she has already been assigned to a home. Upon arrival, there is a period of 90 days for the new employer or recruitment office to take the domestic worker for mandatory medical tests and process her visa.

The recruitment office in Oman is responsible for matching prospective employers with domestic workers. The employer is responsible for paying the recruitment office for their services, which include the flight ticket and visa costs of the domestic worker and a fee for the work of the recruitment agency. The fees that employers pay to the recruitment office vary, as do the workers’ salaries, depending on the nationality of the domestic worker:

Neither the recruitment office’s fees to hire a domestic worker in Oman nor the domestic worker’s minimum salary is regulated. Salaries that are regulated are only for workers whose origin country has a bilateral agreement with Oman stipulating a minimum salary for a domestic worker. Sierra Leone does not have a bilateral agreement with Oman for the protection of domestic workers.

Furthermore, the lack of regulations around recruitment offices means the fees charged to employers to hire a domestic worker are extremely high compared to the minimum salary for Omani citizens of 325 OMR (approximately US$844). There is no transparency around the fees and how they are broken down. These fees are a high investment for employers, incentivising potential worker abuses such as salary reductions, increased workloads or longer working hours, as well as requesting “release money” for the domestic worker to return home before the end of the contract.

Few days ago I tell boss that I’m sick so let them please help me to go back in my country he said and then I ask him to take me my office the office doesn’t allow me to go said so stay outside for so many hours and I talk to my boss to come and pick me them they said they’ll give me other house to because I say no the mother for boss tell me that they’ll take me in police after then my boss hit me 😭😭

Failing Pre-Employment Medical Test

As an employment condition, domestic migrant workers must undergo a pre-employment medical test to identify particular contagious diseases (e.g. HIV, TB) and pregnancy. These tests, it has been well documented and reported, are discriminatory – in particular HIV and pregnancy testing. In addition, the confidentiality of personal data and privacy is not respected.

It is also important to point out that, according to the Domestic Worker’s contract, the recruiting office is responsible for paying the worker’s return ticket within 180 days from arrival if she “has a disability of a type that will render him/her unable to commence the assigned work” and if she “has an infectious or chronic disease or a mental disorder”.

During this project, we supported the repatriation of four women who did not pass the pre-employment medical test, all within the same period of time. Upon failing the medical tests, the offices demanded that the women or their families pay for their return tickets. It is also worth noting here that all of these four women were recruited through the same recruitment office in Oman and three of them had the same recruiter in Sierra Leone.

Treatment of Domestic Workers by Recruiting Offices

Treatment of domestic workers by recruiting offices varies but, in general, mistreatment is widespread. Throughout the project we documented women being subjected to threats, physical and sexual violence, wage theft, and denial of food and water by staff or owners of the recruitment offices (see Threats, abuse and harassment, and violence, living conditions, wage theft).

“Because am very sick i ask them to take me to the hospital they refuse so they lock me in office with no food”

Oman issued a standard domestic work contract in 2011 regulating the relationship between the employer and the domestic worker. This contract is the same for all domestic workers, it is only the personal details and the salary that vary. However, this work contract is unconscionable, offering minimal protection towards domestic workers. It is rarely signed by either the employer or the domestic worker, and it is mainly used as a tool by employers to keep domestic workers working for them, regardless of working and living conditions, for two years.

Absence of a Work Contract

A work contract is a fundamental framework regulating the relationship between the employer and employee, which states the rights and responsibilities of both parties. The contract is to ensure that both the employer and domestic worker have a clear understanding of what is expected. The Standard Domestic Work Contract in Oman “[…] is not valid unless electronically or physically signed by both parties”.

From our community of Sierra Leonean women in Oman, only 22% confirmed that they had signed a contract in a language they understood. In the case of Oman, this would be in both Arabic and in English. From the rest of the women, 54% said that they did not sign a contract in a language they understood while another 15% said that they do not know whether they signed a contract or not. It is also important to note that from the 390 domestic workers that we had conversations with, and from all the documents that they shared with us that they had a copy of (screenshots on their phone), no one was able to share a copy/screenshot of their contract.

With no work contract in place, the domestic worker is vulnerable to working under conditions that best suit the employer, creating vulnerability to forced labour and other forms of exploitation and abuse. For example, we documented that some of the domestic workers’ responsibilities included different tasks that ranged from well-defined domestic work to work that falls outside the scope of domestic work, such as animal care or agriculture. Additionally, 65% of the women reported working for more than one family. Working for families other than your employer in Oman is not only prohibited, according to the Ministerial Decree 189/2004, but also it sheds light on the extent to which employers will make use of their domestic workers.

“I was working for five families in the same compound l do all the house work cleaning four rooms and four birthrooms (sic) and a palour but i clean all the five families compound i throw dirty for all the people in the five different houses i cook an wash plate than (sic) i wash their mum i laundry and iron the day i said am tired to wash their mum all of them avoid me then i call in the office mama Maha*said i should do it .i said i do all the house work for 5 family she said she knows let me work i said i don’t want his place family were just coming everyday she said no office for me if i dont work they will take me back to my country. Them i cryed (sic) when month finished the 26 i ask them for my money they said they give me 70 rials i said no this is not the money u should give me is 90 rials they said the balanced (sic) is for the office”

In addition to the absence of a work contract, we also documented at least six (6) cases where the employer renewed the work contract and her visa without the domestic worker’s approval. Under the kafala system, the employer has all power over the domestic worker, including having the ability to renew her contract without her approval or presence. As with the first contract, this contract is also not signed by either the employer or domestic worker nor shared with the domestic worker.

Domestic Workers’ Work Contracts

The Standard Domestic Work Contract used to employ domestic workers offers minimal protection from exploitation. In addition to being minimal, it also contains unfair clauses or threatens the well-being and safety of domestic workers. These clauses in the Standard Domestic Work Contract include:

- Termination of contract. The employer has the right to terminate the contract for any reason, but the domestic worker can only do so “if it is proved that he/she has been abused by the First Party [the employer], or if the latter violated any of the basic legally acknowledged obligations of the provisions of this contract.” However, in reality, domestic workers do not have access to a mechanism to raise complaints in case they haves suffered abuse or the employer violated any of his/her obligations, rendering them unable to terminate the contract. For example, when we assisted women in filing complaints against their employers or we directly filed complaints on their behalf, terminating their contract was not an option. Instead, they were returned to their employer with no justification (see Access to grievance mechanism)

- Changing employers. A domestic worker cannot change employers unless her current employer agrees. In the work contract, there are no protection clauses to allow the domestic worker to transfer employers. In practice, to change employers domestic workers need to have permission from their employer and already have another employer willing to take her under his/her sponsorship. However, this rarely happens. Among the group of 390 women that we spoke with, we did not encounter any workers who had been able to change employers legally.

- Health insurance. In the Standard Domestic Work Contract it is stated that the employer “shall commit” to “bear the medical care expenses” for the domestic worker, but it does not require the employer to provide health insurance. This means that the employer should cover medical care expenses if it is needed, but not that health insurance is mandatory. From the 390 women we held conversations with, we documented a large number of women who had requested that their employers take them to see a doctor. Employers responded by either ignoring their requests and providing Panadol, or taking the worker to a clinic but having the worker bear all expenses. In addition, it is stated that it is obligatory for the employer to “provide death and work injuries insurance” for the domestic worker, protecting the employer from any liability.

- Probation period. The domestic worker “shall be subjected to a probation period for 0 days and shall not exceed 90 days”, but the worker does not have the same right to a probation period or the right to return to the recruitment office if she wishes to change employer.

- Working hours. The contract does not specify the maximum working hours within a 24 hour period, leading to the majority (80%) of domestic workers we surveyed working between 16 and 20 hours a day and always being ‘on call,’ especially when there were children or elderly people in the house.

Again, it is important to note that while there is a standard contract provided by the Government to the employer, a worker has never been able to share with us a copy of her contract, putting in question its validity.

“No 😭 communication,no time to rest, everyone will shout at u when u clean they will use there (sic) big toes and asked u to clean again,I washed clothes even for the doughters (sic) from there (sic) husband home 🏡 every day, I take care of domestic animals,any things from out side heavy or light they will called me,I sleep on the floor in the store is not really easy.”

Confiscation or Retention of Identity Documents

The ILO Forced Labour Convention, 1930, considers the confiscation or retention of workers’ identity documents as an abusive practice, increasing the vulnerability of workers to becoming victims of forced labour. Additionally, although retaining the passport of a domestic worker does not necessarily indicate an intent to commit abuse, it does have a crucial impact on the worker’s perception of her freedom.

In our research, we found that the practice of withholding a domestic worker’s identity documents – both passport and civil ID – by both the employers and recruitment offices, was commonly practised and accepted.

Several reports and articles have reported that the Ministry of Labour circular No.2/2006 prohibits employers from withholding migrant workers’ passports. However, we have been trying to find this circular without success. We conducted an in-depth search both in English and Arabic and throughout government websites all to no avail. We also tried to reach the Ministry of Labour via phone for clarification but we were not able to get through. Therefore, without seeing a government document prohibiting employers from withholding passports from domestic workers, we would not like to assume that it is so, but rather state that it is not clearly prohibited.

Researched throughout the Arab States, one of the reasons for employers to withhold the worker’s passport and/or civil ID is because of the fear of domestic workers leaving the employer to work somewhere else. However, these motives in the context of Oman are not realistic as a worker is not able to change employers without the existing employer or recruitment office transferring her visa sponsorship, even if she possesses her passport.

Survey responses indicated that 84% of the women did not have their passports with them, while 13% reported that they did have their passports with them. Of those that did not have their passport, 85% stated that their passport is with their employer, 8% with their recruitment office, 5% stated that they do not know where their passport is and 1% stated that they had lost it.

However, there are contradictions between the survey responses and our conversations with the workers. A higher number responded positively in the survey than in our one-to-one conversations with 390 women (99% from a sample size of 390 women did not have their passport). It may be that access to their passports changed, or that they considered a photo of their passport sufficient to answer positively. Furthermore, of those we supported through repatriation, only five had possession of their passports. Therefore, we believe that the number of women who did not have their passports with them might be higher than the survey indicated.

For those that actually had their passports with them, it was for two reasons: Their employer or recruitment office had kicked the worker out of the house or office right before the end of their two-year contract and filed “absconding” charges against the worker to avoid paying her return flight ticket, or because the worker was able to take her documents with her before leaving the employer.

The widespread practice of confiscation and withholding of domestic worker’s identity documents severely restricts the women from bargaining over the terms and conditions of the job or working conditions if she is still with her employer, or, if she has left the employer, from returning home (assuming no charges were made), seeking medical attention, or sending or receiving remittances. Without documents, they were also unable to access key government services, such as the amnesty registration.

“dont have any documents, cant go because my sponsor has my documents”

The women were also consistently concerned about when and where they might be asked to present identity documents. This fear, real or not, leads to most women reporting that they are wary about leaving the house where they stay for fear of encountering the police and being asked to present documents they don’t have. In addition, a group of women reported that they did not travel on buses, which are considerably cheaper than taxis, as they had heard identity documents were required to board.

It is important to note that in addition to the multiple challenges that domestic workers face when their passport is confiscated and withheld, the psychological implications that domestic workers are subjected to are beyond this research but present. Through our conversations with the women, we often observed the state of feeling powerless, trapped and helpless among the women for not having their passports with them. In addition, we also documented multiple cases where the passport was taken in Sierra Leone by airport officials upon returning due to the inability to pay the health declaration fees, in these instances, we also observed the negative impact and psychological consequences it had on the women.

“Up to now I go to the airport and they tell me I should pay $80 dollars to collect my passport. My passport is still with them in the airport”

Wage Theft and Salary Deduction

Wage theft refers to the unlawful and intentional non-payment, partial or complete, of a worker’s wages or entitlements by their employer or recruitment office for work carried out. Wage theft can also refer to deductions taken from a worker’s salary for no valid reason. Salary deductions include when the payment is reduced, or when the salary is delayed, for example, paying every 6 weeks instead of every 4 weeks.

“I got paid through by the sponsored , she sometimes paid me fifty five real (sic) for only one month sometimes I don’t got (sic) paid”

Wage theft is a common practice of systematically forcing workers to keep working in the hopes that their dues will be paid in full. This practice not only denies the worker a fair payment for their work but is often used to limit the worker’s ability to leave from fear that, if they left, they would lose their back wages. The workers’ ability and hopes to return home are tied up in back wages, as they often do not want to – or are unable to – return without the money they have earned. In almost every case, workers had plans for how they would use these wages, generally to pay off debt (often debt incurred to travel to Oman), start a business, or support their families. Wage theft, which keeps workers bonded to their work and forced to work, is a practice that can constitute debt bondage and/or forced labour.

“Maybe I will have my salary after two months and I will paid 70 Oman rials. Yes, because they know I am weak and their nothing I can do to them. So they too advantage of my situation”

From the 469 Sierra Leonean women we surveyed, 60% were victims of wage theft. In total, 41% did not receive their salary every month and 59% did. From the 59% that did receive their salary every month, 32% did not receive their complete salary. In addition, during our conversations with the women we noticed that it is common for the employer not to pay the domestic worker for the last 2 or 3 months before finishing the contract or shortly before she is about to return home.

Working Hours

Ministerial Decree 189/2004 for domestic workers and the Standard Domestic Work Contract mandate a one day off per week, however, they do not define maximum working hours or overtime payment.

In our research, we found that 99% of the women work without any days off. Long working hours are also a widespread issue: the majority of women (80%) worked between 16 and 20 hours a day with 87% starting work between 4 and 6 am, and 84% ending between 10 pm and 1 am. A total of 63% had one break per day while 30% had none. Of those that had breaks, 55% had between 1 and 1.5 hours break while 30% had two hours.

“No breaks, unless the childreens (sic) sleep”

These working conditions have led to extreme exhaustion for the vast majority of this group of Sierra Leonean women, as they would for any other person. This has possibly led to the deterioration of their physical and mental health, which we observed in several women to the extent that airlines did not allow them to board. This extreme exhaustion was one of the main drivers for the women to leave their employers, simply unable to continue working in such conditions.

“I was sick to the extend that I was unable to talk, they did not take me to hospital I had to use hunger (sic) and garlic to treat myself. Then later he transferred me to work for another family. When I got to that family, I fell sick again, I taught (sic) I was going to die. So they took me to hospital but thesame (sic) day I came back from hospital, I continued working they could not allow me to rest. The sickness continued that I lost sleep, I don’t sleep again. At a point I was going insane I don’t know what I was doing again, I think right I was behaving like one who was going to run mad. I shed tears each time I remember it.”

Restriction of Movement and Isolation

Restriction of movement and isolation puts the women in a very vulnerable position. Not only that it isolates them from accessing any potential form of support, help or assistance if needed, but also further isolates them from their families and loved ones.

“She said I can not use my phone in a month I only use it once in month”

In our research, we found that the women were restricted from both leaving their employers’ house or their office and isolated from accessing communication with the outside world. When asked if they were able to leave their employers’ houses by themselves, 91% say that they are not able to.

“He said I came to work, not to speak with family”

In addition, 49% of the women were forced to hand in their phones or SIM cards to their employer at some point, 21% stated that they were not allowed to use their phones, 38% that they were allowed while 41% were allowed to use their phones sometimes. As for Wi-Fi access, 50% of the women reported they did not have access, 24% had access sometimes and 26% had access. Those without Wi-Fi access rely on prepaid data which they must pay for access to the internet. On the other hand, if their wages are withheld or if they are not able to leave the house to purchase credit, no form of communication with the outside world exists.

“Sometimes when I am sick and she ask me to do something if I tell her I am sick she will get angry instead of giving me medicine she will disconnect me from wifi”

Furthermore, 26% of the women reported that they were locked or had been locked in a room at some point, some stating that they were locked in for days and some without basic necessities, such as food and water. During our conversations, it was noted that employers and recruitment office agents would lock their domestic workers in as a form of “punishment” for behaviour that was not accepted such as asking for their salary, refusing to do a task, requesting to return to the office, or refusing to work due to sickness or exhaustion. In other cases, workers reported that their employers or office agents would lock them in rooms if they thought the woman was going to try to leave the house/office. These forms of punishment usually lasted for a couple of days.

“They lock me in my because when I tell them that i want to use my phone they said no i should use phone so I deside (sic) to use phone they bit (sic) me and lock me up”

“Some times they use to locked me the room because when they to out and live me alone then they disided (sic) to locked (sic) me in the room”

Living Conditions

Ministerial Order No. 189 of 2004 regulating working conditions of domestic workers states that employers are required to provide “appropriate room and board” for the domestic worker, and the standard work contract for domestic workers states that the employer shall commit to “provide decent food and accommodation if the nature of work requires it”.

However, we often found that the provided living conditions of domestic workers were not appropriate. In our findings, 65% of the women had their own room, which was often described as a storage room or a small room. The remaining 35% of the women did not have their own private room and stated that they were forced to sleep in the kitchen, living room or in the bedrooms of the children or the elderly people they cared for.

Often, whether in their own room or not, they slept on the floor. The living conditions were reported by the participants as humiliating and unsafe, and with no privacy. In one instance a woman shared how they did not allow her to lock her room or the bathroom and how men in the home would open the bathroom door and look while she took a shower.

“Two freezer inside the room. Their clothes inside the same room others items are there in the same where I sleep. Father, mother, children come in going out for the rest of the day even when I want to sleep. No sleep closing the door very hard, sometimes even I close the door they will leave it open if I talk about that they told me that it is not my home.”

“My real sponsor gave me out to another family. This family never made provision for a maid room. My room was like a dumping ground, it was a parking store. It’s was even difficult for me to get to my bed because there was no space. I don’t breath well in that room because of the loads there. Intact (sic) it was a terrible experience in that house.”

Our research also documented how the women did not have the ability to satisfy basic human needs, such as food and nutrition, along with hygiene products. Of the 469 women, 58% reported that their employer did not provide them with sufficient food, while 4% stated that their employer did not provide them food at all. Some women stated that they were only given rice and tea, others stated that they were expected to buy their own food and soap, while having limited income and ability to leave the household of the employer to make purchases.

“She gave me just little and that little also is what they have eaten and left”

“Well thank God am the one that cooking for them so I have the small opportunity to eat”

Some women reported that they ate only leftovers. Others provided videos of their food which showed plain white rice with no salt or white rice with sugar and instant coffee or an empty refrigerator.

Threats, Abuse, Harassment, and Violence

“I was called a slave and should only work like a slave and no privileges should be given to me.”

Sierra Leonean domestic workers in Oman are highly vulnerable to physical abuse, threats, bullying and violence. Severe instances of violence, including rape, flogging, “pinning” of skin and pulling of teeth have been documented.

“Mam, they pinning me right now, there is no way I can feel my hand. It is so cold and so hot in my bones. […] My hand, I am dying, painfully. I am still locked up, mam I am tired”

“One morning when i finished working i was feeling weak so i decided to take rest but unfortunately i slept off so when my madam meet sleeping she started shouting at me, using abusive language on me she said that am here to work if i finished working i should look for another work to do that i should not rest.”

Verbal abuse including humiliation, insults, and discriminatory remarks were also very common. 77% of the women stated that they were either verbally discriminated against, felt humiliated, or were insulted by the employer, his/her family, or recruitment office staff. The most common verbal insults included being called a ‘slave’ or a ‘dog’ or Arabic insults, but women were also humiliated based on their physical characteristics (body or hair) or body odour.

“They said am smelling and my room have bad smells and we don’t have the same color I am a slave”

“They tell me that I smell, if I pass they will cover their nose. I feel terribly bad about it because I know I don’t smell. Sometimes my madam will ask me if I poo on my body that everywhere is smelling. Sometimes in presence of her children, she will ask me if I brushed my teeth. And I tell her yes, she will say I should go and brush again because my mouth is smelling.”

In addition, the women stated that they felt humiliated when their belongings were searched. Although the reasons for searching their belongings were different in every case, a common reason was that something was “missing” from the house and the employer or family members needed to check her belongings. Of the 469 surveyed, 55% reported that their belongings were searched at some point.

Threats are often used as a way to ensure that the worker remains compliant or obeys what is being requested. Employers most commonly threatened to call the police and have the worker arrested and deported, or to lock her in a room if, for example, she complained about work. Others included threats to be beaten, especially by recruiting office staff if she would return to the office. Although most requests were to keep the worker compliant, other threats included non-payment and threats of a sexual nature. Many of these threats had real consequences and were more than mere threats.

“My boss is not good some time he want to sex me when I tell my madam she said that if I tell anyone they will kill me that why I live the house and come outside”

“Living is not good day [they] beat me he say he pull my teeth sometime he will not give me food”

In regards to physical abuse, more than half of the women experienced physical abuse. Our research indicates that 57% of the women have been hit, slapped, pushed, or physically harmed by either their employer or a member of the employers’ family. Some of the women reported being physically assaulted and abused by the sponsor and then threatened with ‘the police’. Other women noted that they were beaten and threatened using the fear of wage withholding. The majority of those that experienced extreme physical abuse provided videos, audios and photos of their bodies or the incident itself.

“In my first house, sponsor and wife beat me up. Hit me with steel in my back, hip hurts when I sit down now. Hip bone and back pain. Sponsor choked me. I defended myself with an iron.”

“they [her employer’s family] poured dirty water on my head because I was late to come because I was praying. They [her employer’s family] slapped me, they [her employer’s family] took me to another house”.

“When my baba came from work [..] he would beat me and slap me […] so the last thing I see from my employer, me and my madam we were cooking in the kitchen he used a spoon from the hot oil and put it in my hand, this is the last thing they did to my body, so I decided to ran away.”

Along with the physical abuse, 27% reported that they had experienced sexual abuse. Of those that disclosed the perpetrator, they indicated that it was an employer or a family member. Furthermore, 9% of the women were not sure if they had been sexually assaulted or abused.

“Their son rape me and later took a knife for me”

Health Issues / Health Insurance

“They said only a citizen can get access to medical”

The health of many of these women was in a dire condition, both for those who were with their employer and those who had left. For the women still in their employer’s home, the main complaint was extreme weight loss and inability to work due to exhaustion. We believe this was due to the long working hours and the minimal nutrition that most women received. Other health issues included inability to walk, swelling of feet, inability to retain food, no bowel movement and vomiting of blood as well as workplace injuries, such as broken bones and severe skin damage due to burns. For this group of women, the response of the employer varied, but it was common for the employer to provide Panadol and ignore other requests. They were also often told by their employer that they were not really sick and that they just did not want to work.

“they don’t want to know that you are sick, they pay you end of the month but you must still work. no rest no day off. if you are lucky they give you panadol (i am lucky but i have to ration the panadol they give me). can’t go to doctor because don’t have documents”

“They did not allow me to go out, they said they come with me to work not to sick”

For those that were outside, there was a lack of access to medical care. Most were not able to see a doctor because either the women did not have any form of identification, required to be seen by a doctor, or because they lacked resources to see a doctor such as transportation and consultation fees.

“Because I don’t have money to pay” – when asked why she does not have access to medical care

The findings in the previous sections report on issues related directly to human trafficking or forced labour. In this section, we report on additional challenges that we documented among the group of Sierra Leonean women in Oman that are interlinked with additional vulnerabilities.

Ability to Leave the Country and Return Home

The right of return is a principle under international law where an individual has the right to voluntarily return to their country of origin. It is also stated in international human rights law that all victims of trafficking are entitled to return to their country of origin and it is the obligation of the country the victims are in to allow those who wish to return to do so.

In Oman, the employer has sole control over the domestic worker’s ability to exit Oman, unless the domestic worker has her passport with her and no “absconding” files have been charged against her. However, domestic workers who are victims of human trafficking or exploitation who leave their employer usually do not have their passports with them, and often “absconding” charges are filed against them, rendering them powerless and unable to leave. Being in this helpless situation keeps domestic workers trapped within this system. In many cases, women choose to stay in abusive working conditions because they have no other viable options, and this ultimately fuels the continued presence of exploitation and abuse in the country.

Domestic workers, trapped in this situation, are often waiting for an amnesty to return home. In 2021, Oman put in place an amnesty for migrant workers whose visas had expired and/or who had left their employer to be allowed to leave the country without the employer’s consent and without paying overstay fines. However, for domestic workers to obtain this amnesty they had also to have “absconding” charges filed against them, otherwise, they did not qualify to receive amnesty. This left a large number of women trapped and unable to return home.

“It is ok for us because like as you can see it is not really easy because we have set our minds and souls that we are going home. We are really sad but we are patient.” […] We stay and wait again to see what Allah can do for us”

If a domestic worker is covered by an amnesty and is allowed to return home, buying her flight ticket is also another hurdle that is insurmountable without outside assistance. Unfortunately, the Embassy of Sierra Leone in Saudi Arabia, responsible for Sierra Leoneans in Oman, has no budget for flight tickets to repatriate its nationals. This means that even individuals who are legally able to leave the country are often unable to, and rely on organisations like Do Bold for support with flight tickets (see Safe and voluntary return).

During this project of 22 months, we saw only 2 Sierra Leonean women leaving the country without the employer’s consent. In both cases, the workers had their passports with them and no “absconding” charges had been filed against them.

When asked if they want to return home, from the complete verified sample of 469 women, 75% stated yes, that they want to return to their home country ‘as soon as possible’, 23% ‘not yet’ and 2% ‘I do not know.’

Raids, Detention and Deportation

During our work on this project, we were made aware of two raids. Raids are conducted throughout the Gulf countries to deport undocumented migrant workers. These often take place at night and outside on the streets, but it is also common for raids to happen inside buildings that are known to house migrant workers.

One of these raids took place in an apartment where approximately 13 women were staying. It happened at night during Ramadan 2021 when the police entered and detained the women without any legal justification for the arrest and without first checking their legal status. Once arrested, the women were taken to a detention centre where they had access to their phones once a week. They reported that no information was given about why they had been detained and no formal charges were made in either written or verbal form.

All the women in the group that was detained in the raid had absconded, however, some of these women had amnesty and were in the process of repatriation. All women were eventually deported. In some cases the employer had to pay the return flight ticket, and in others the flight ticket was requested by the police from the worker or worker’s family. It was not clear why in some cases the employer paid for the worker’s ticket and in others not, but we assume that it was related to “absconding” charges and the registration of amnesty.

“Nobody tell us that our baba block us they only tell us if we have our tickets so if you can tell them that we have tickets so they can free us. This place is not good for us we suffer everyday no food, and someof (sic) us are sick so please help us […]. We are begging you please [crying].”

Most workers that are detained are deported without their belongings, including their savings if they had any. Only in those cases that we are aware of and able to assist on can we get their belongings to the detention facility and support them with their air ticket home. However, this is not the norm.

In regards to detention, we came across cases where domestic workers were spending long periods in detention without any justification and without the Embassy of Sierra Leone in Saudi Arabia being informed. In two examples, one woman spent 7 months in detention and another woman 16 months. In both instances, the embassy had not been made aware and no formal charges had been filed against the women. In both cases, we facilitated the travel documents and provided the flight tickets home after we were told by prison officials that this was the only way that they would be able to return home.

Discrimination

Sierra Leonean domestic workers reported consistent racial discrimination from employers, generally in the form of verbal abuse (see Threats, abuse, harassment and violence).

“They do intentionally insult me because am a black lady.”

Sierra Leonean women noted that they were also discriminated against based on their nationality. They reported that the treatment received at governmental offices differed between different nationals from African countries. For example, support for Sierra Leoneans in governmental office was absent compared to support given to nationals from Ghana or Nigeria. In one instance, a group of Sierra Leoneans was not allowed to go into an office without an explanation and waited throughout the day to enter while nationals from other African countries were allowed to enter. This group of women had to return another day.

Furthermore, the wage payment based on the nationality of the domestic worker is discriminatory. The salary suggested by recruitment offices in Oman promotes a lower salary for Sierra Leoneans compared to other nationalities who perform the same work. There is no regulation stating the minimum salary, and cases where some domestic workers receive a higher salary than their counterparts arise because of existing bilateral agreements between those countries and Oman to secure higher wages for their nationals.

Experiencing Exploitation when Leaving the Employer

The majority of our community of Sierra Leonean domestic workers left their employment due to exhaustion, wage theft, abuse and lack of medical care. Many also sought help to leave their employer. We encountered groups – comprised of Sierra Leonean and other nationalities – providing support for these women to leave their employers. However, this is more of a service as it is charged for profit. In some of these cases where the women left with the support of someone else, they found themselves in another exploitative situation. For example, some were provided housing and food in exchange for working in prostitution. Others were put in other temporary homes, working as domestic workers, where part of their salary would be given to the person who “helped” them leave their former employer.

“I stay with one madam. I have been helping this madam for doing house job just because she rescue me … I asked him to go and ask for ticket price and he said ticket is not available until next week, or two weeks or three weeks time, just because they want me to help them doing job without no payment. So this is the problem. This is the advantage they have been seizing on me here now.” – worker staying with a family who ‘rescued’ her after she was kicked out of her sponsor’s house at the end of her contract

“They tell you they will help you find a job and then charge you for that. Then, if you are working for a few months and need to rest — they will charge you 40 rials for a few days rest. If you refuse to pay, they will drive you out.” – woman exploited by members of the Sierra Leonean community

Human trafficking and exploitation involve different forms of human rights violations. In most human rights international treaties, it is stated that states are required to provide access to remedy, even if violations are not committed by states. Access to adequate and appropriate remedies, protection and justice for this group of women, unfortunately, has been close to non-existent.

The Kafala System

The kafala system is the general term for the employment visa system used across the Gulf region which ties a worker’s visa and status in the country to a single employer. For domestic workers, their sponsor is their employer. The legal status of the worker is thus delegated from the state to an individual. This delegation of responsibility creates a dependency relationship where the employer has unbalanced and unchecked power and control over the worker, allowing for multiple issues to arise from this relationship. For example, employers can file an “absconding” case against the worker, even if she has not left her employer. They can also renew her contract without the approval of the domestic worker or can bring charges, such as theft, against the worker without facing scrutiny themselves.

If a domestic worker is a victim of exploitation and other forms of abuse, her only option is to leave her employer. However, under the kafala system, where there are no proper grievance mechanisms, if she leaves her abusive employer, “absconding” charges will be filed against her and she will be identified as a criminal rather than a victim of human trafficking or forced labour. On the other hand, knowing that if she leaves her employer she will be detained and deported, she may feel that she does not have an option but to stay in an exploitative situation until her contract ends.

The (legal) dominant/subservient relationship created from this situation amounts to forced labour or involuntary servitude.

“Absconding” Charges (“runaway”)

According to Decree 189/2004, employers have to notify the relevant authorities if their domestic worker has left their employ, also known as “absconding” or “runaway”. Under the kafala system, “absconding” charges are filed against a domestic worker who has left her employer, no matter the reason why she left. These charges mean that if she is detained, she will be arrested and deported without any proper investigation made into why she left her employer.

“Absconding” charges are one of the kafala system’s greatest hindrances in preventing and addressing human trafficking and forced labour. It prevents the Omani government from identifying victims of human trafficking and providing them with appropriate protection and access to remedy and justice. Once “absconding” charges are filed against a domestic worker, she will be identified and treated as a person that has committed an offence. No investigation for the reasons why a domestic worker left her employer takes place. There are no further mechanisms to identify her as a victim of human trafficking, exploitation or any other form of abuse. Thus no one is held accountable.

“One house I worked for five months I was suffering no better food I decided to run the knew I wanted to run so they locked me up for a week, until the other week they easy (sic) me little I continue to work for them so they have my passport and I jumped and run away”

Domestic workers who are exploited, facing abuse or extreme isolation with their employers or with the recruitment office, have very few options to improve their situation. For many, their best option is to leave. Despite leaving an exploitative situation that should be reported to the authorities, the majority do not report it due to fear of being returned to the employer.