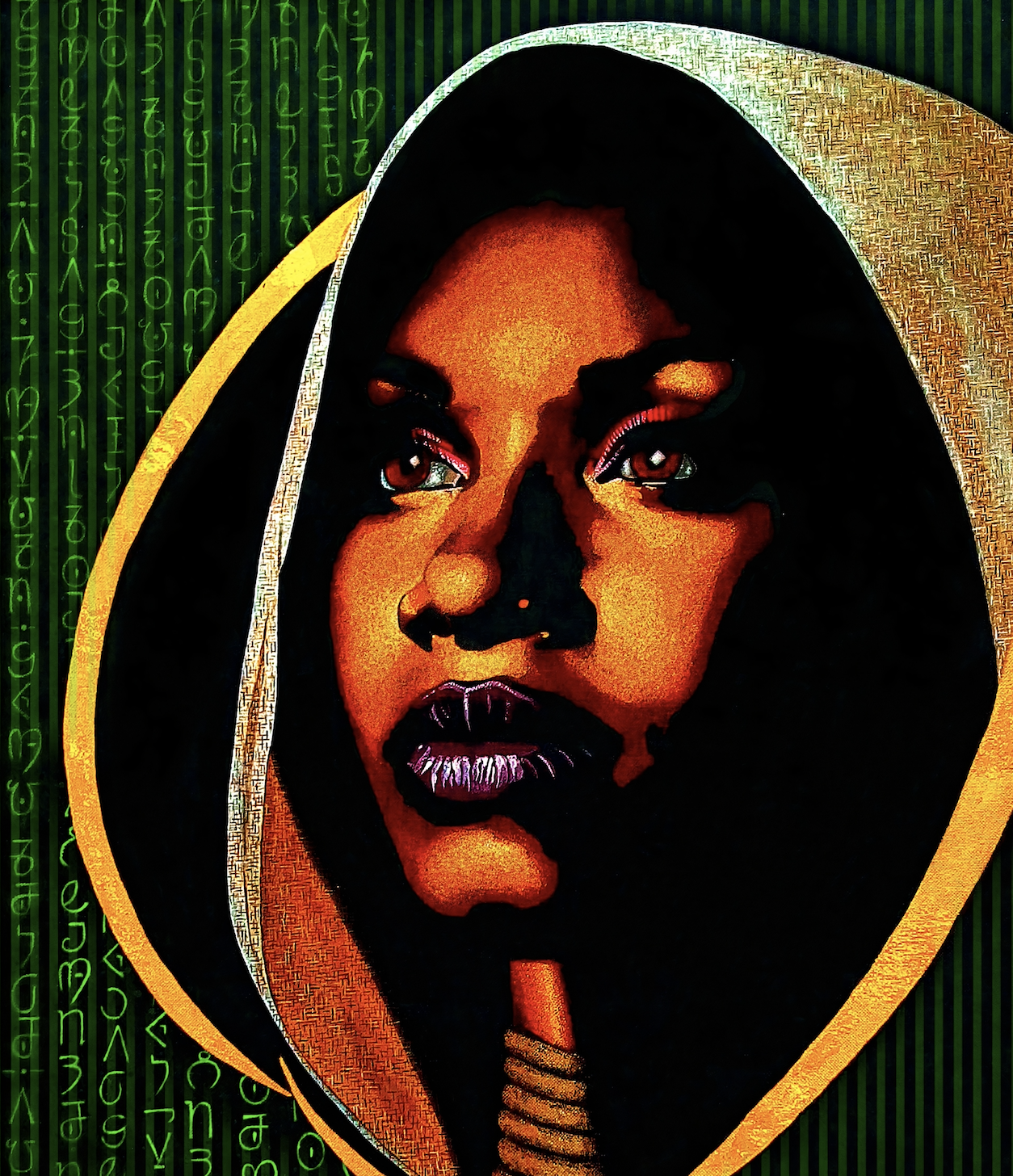

Aisha's Story

Aisha’s Story looks at issues often present in recruitment offices in Oman. It highlights how recruiting offices are exploiting domestic workers and are not held responsible for the repatriation of domestic workers if a medical exam is failed, nor are they held accountable for wage theft and exploitation.

Aisha’s mother and father died, leaving her and her 10-year-old sister on their own. More than anything, Aisha wanted her younger sister to go to school. One day, a neighbour told her about her uncle who helped people work abroad. She told her stories about people her uncle helped who had now made a lot of money and could build houses and gain various possessions. She told her she was sharing this information with Aisha because she felt pity for her. Aisha decided to pursue this opportunity, and the neighbour introduced her to her uncle Emmanuel*. Emmanuel lived in her city and his boss, Sayid*, in the capital, Freetown.

He told her she would make US$500 a month as a domestic worker in Baghdad, Iraq. After 2-3 months, they would increase her salary to US$600 a month. To go, she had to pay US$1,000 for documents, a medical test, a visa and a ticket. Aisha decided to go so she could make money and send it back for her sister’s education.

To raise the money to pay Emmanuel, she worked odd jobs. She saved US$300 and also asked her mosque to help – the members contributed money and gave her US$300. With US$600, her recruiter said that would be enough and they began processing her paperwork. They told Aisha to tell the passport office that she was 24 years old. At her actual age, 22, she might have been considered too young to get a visa, they said. Aisha was also taken for a medical exam, which she passed.

Then Aisha was on her way. She left her sister with her neighbour and planned to send money back every month for them to take care of her.

Aisha first travelled to neighbouring Guinea, where she stayed for 17 days before receiving her visa and air ticket. She believed she was on her way to Iraq. In January 2021, she landed in Oman.

“I called [my recruiter] … I said, ‘I did not say I would come to this country. You told me you would [send me to] Baghdad. And now I’m in Oman,’” she said. “When I messaged him, he would not reply me. When I call him, he would not pick [up] my call again. He don’t care about me again … I spent my money without no good information. The agent duped me. He ‘ate’ my money. He lied to me.”

In Oman, Aisha was taken to a recruitment office. She asked questions and explained this was not the country she paid to come to.

The office agent told her, “‘If you don’t want to work, pay me the money I spent for you.’ I said, ‘Which money? I spent money. Call the agent and ask him.’”

The office agent told her that her salary would be 80 Omani rials, the equivalent of US$208, nearly US$300 less a month than the wage she had been promised. With no money to return, Aisha was placed with an employer and began working.

She cleaned, cooked and ironed in her employer’s house in the morning and in his mother’s house in the afternoon. She worked 18 hours a day (from 5 am to 11 pm), every day. After 27 days, her employer took her for the mandatory medical test needed to finalise her visa. She failed. Unable to secure her visa, the employer returned her to the office.

The office agent told Aisha she must give her the money she ‘spent’ on her and pay for her own ticket back. When Aisha was unable to, the office agent sent her to work short-term in people’s homes. She told her to tell anyone who asked why she was working short term that she had passed her medical exam but was working in different houses while her sponsor travelled.

The agent told Aisha that, within three weeks, she would earn enough for a ticket. After three weeks, Aisha returned to the office with her wages in hand, but the agent kept her wages and continued to ask her for ticket money. They sent her to work again for two weeks and, again, kept her wages. When there was no short-term work for her, Aisha spent days in the office and they made her pay for food.

After her second short-term placement, Aisha got in touch with Do Bold. She told us her story, and the story of two other Sierra Leonean women who were in that office with her, both of whom had been recruited by the same two people in Sierra Leone, and both of whom also failed their medical test.

Without money to send home for her sister’s education and basic necessities, Aisha was sick with worry, afraid that her sister would resort to begging for food and then be taken advantage of by ‘wicked’ men.

“I left my sister in Sierra Leone to come and find money, because of her, because I need my sister to [get an education.] Now I came here, I don’t have the money. … Now, he asked me to give the ticket money. If I have the ticket money he will [let me go]. I don’t have money. I don’t have any money now. Please, ma, help me.”

Do Bold communicated with the office on behalf of Aisha and her friends. They agreed to release the women if we provided the tickets. Within two weeks, Aisha and her two friends were on home soil.

Each one received a “Soft Landing Kit”, US$120 to help with basic resettlement expenses. Aisha used hers to buy food, necessary personal items, and to pay her sister’s school fees. But, with the money we gave her running out, and having used all her savings to pay to go to Oman, Aisha soon fell into despair.

“I need you to help me, to catch [this man for me]. Now, I don’t have anything … Now, since yesterday, although I’m really happy [to be home], I started thinking, ‘If this money finish … who will give me money again?’,” she said. “Because no one-no one-will help you. Because they will say, “Ah! You went to Arab country. You didn’t bring money?’ They will start to laugh at me, mock me.”

Determined to get justice, Aisha provided Do Bold with detailed information about her recruiters, which we passed along to the Government of Sierra Leone. She also took the information to the police in her town. They detained her trafficker but refused to arrest him unless Aisha paid.

“If you are poor, they don’t take your case seriously,” she said. “Because that guy have money, they [let him go]. They say I don’t have rights…What can I do because I don’t have money to give them [and he] gave them money. Because I don’t have money, this is the way they treat me. […] They don’t care about me. They give me wrong. Then they gave the man right. They made me feel bad. That day I cried all day.”

The neighbour who originally told her about Emmanuel now avoids her whenever she sees her.

Seven months after returning, Aisha is in a city closer to the capital working as a cleaner for approximately US$30 a week. Her sister is staying in a village with their aunt and attending school.

(*This report uses pseudonyms for all the domestic workers and others mentioned and withholds names for in the interest of their privacy and security)